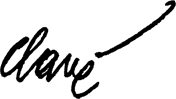

Francisco Goya – Tauromaquia n° 12 « Desjarrete de la canalla con lanzas, medias-lunas, banderillas y otras armas. » 1815-16 Etching, aquatint and drypoint © Museo del Prado, Madrid

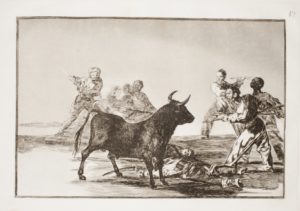

« Corrida » 1951 B/W lithograph

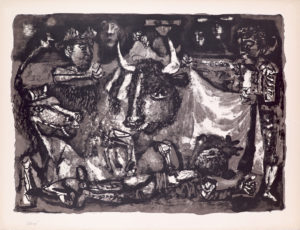

« Corrida » 1951 Colour lithograph

It is not the first time that Antoni Clavé creates a link with the heritage left behind by Goya. With his first works as a lithograph or with themes such as bullfighting or sorcery, Clavé offers compositions inspired by the Spanish Master, of which Lettres d’Espagne (1944) or the plates dedicated to corrida (7 prints between 1945 and 1951) are representative.

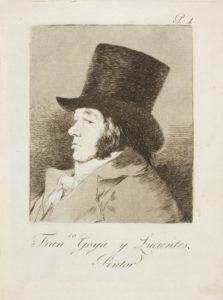

Francisco Goya y Lucientes, ” Autorretrato” 1797 – 1799. Etching, aquatint, burin, drypoint © Museo del Prado, Madrid

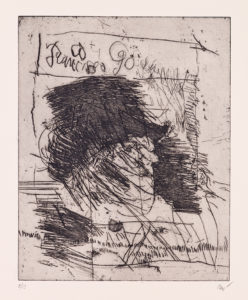

« À Don Francisco » 1966 B/W etching on zinc

While he travels to Barcelona in 1965, Vila-Casas, a Catalonian engraver and friend, initiates Clavé to aquatint and etching; he rapidly masters the technique. The next year he decides to pay tribute to big names of intaglio, Rembrandt and Goya, by using metal engraving only. He appropriates again the technique used by Goya thanks to etching and chooses to reinterpret two plates of the Caprichos. This satirical series of 80 prints constitutes a social critique of Spanish society at the end of the 18th century; it was published in 1799, but soon after withdrawn from the market by fear of the inquisition, before finally being gifted to the king.

The first etching of Clavé is a modernized but still recognizable version of the first print of the Caprichos, which shows a self-portrait of Goya. Clavé hence logically titles the print “A Don Francisco”. The following reinterpretation is at first sight less identifiable. The print Nadie se conoce (Nobody knows each other) bears the number 6 of the Caprichos. The whole series of prints can be divided into several themes, among which the infidelity between men and women, to which the above-mentioned print belongs.

Francisco Goya « Nadie se conoce » 1797-99 (Los Caprichos, plate n° 6) Etching and aquatint © Museo del Prado, Madrid

Several manuscripts from the end the18thcentury are shedding light on the Caprichos. The one kept by the Spanish National Library in Madrid is quite explanatory: “A general, either effeminate or dressed up as a woman, is courting a young lady (…) the husbands are in the background, and instead of wearing hats, they are represented with enormous horns, just like unicorns. For the one who hides well, the horn is straight, for the other one, the horn is twisted”.

At this time, the nobility from Madrid was keen on masked balls. And in this print, Goya is inducing the hypocrisies of Spanish society with the representation of a carnival.

Just like the self-portrait of Goya, Clavé’s composition is mirroring the original print. Clavé is not copying, but rather offers a reinterpretation, a new appropriation. It is though interesting to point out that Clavé chooses this time to keep the original title “Nadie se conoce”. It helps us understand that the composition, hard to read at first sight, is actually very close to the original scene. One need to be really attentive to determine the subject. But once it is identified, it is of no use anymore. Ball costumes have been erased and crossed out. Clavé only kept the masses and the chromatic dichotomy. There is no direct satire in Clavé’s print, the signification of Goya’s oeuvre is eternal and sufficient by itself.

The homage is mainly technical and aesthetic. Clavé shows how well he masters etching and plays around it with a very contemporary approach: he erases the engraving, which echoes the historical gesture of Robert Rauschenberg himself erasing a drawing of Willem de Kooning in 1953; Clavé also crosses out the plate, referring to the drawings of Cy Twombly and the abstract expressionists (the action requires more force but is based on the same process). With this etching, Clavé introduces Goya to the second part of the 20th century and its modernity.

To know more about the printed work of Antoni Clavé, see the catalogue raisonné recently published by the Editions Skira.