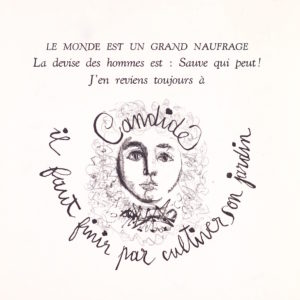

In 1945 Clavé illustrated Carmen written by Mérimée, and edited by Jean Porson. A year later, the editor asks him what text he would be keen on illustrating if he were to participate in a book for bibliophiles. Without hesitating Clavé replies “Candide”. He explains that he would like to express the tragic side of this tale, which is a diabolic representation of human misery. It is a bitter and disillusioned smile that Clavé wishes to express.

Candide was published in 1759. A philosophical tale now globally known, Candide is also a story where the character grows up along the story, and where parody, feelings and picaresque narratives are put together. Voltaire renews, twists and plays around the major genres of the XVIIIth century, and thinks the narratives threads through to the end. He hence leads the readers to an analysis regarding literature as well as human society and its incoherence. Irony enables him to broach different concepts: it is a critic of war, misunderstood religion, lost philosophers, colonialism and a reflection around evil.

In December 1948 the editions Jean Porson publish Candide, with 46 lithographs in black illustrating the book. 10 ‘suites’ on top of the illustrations from the book, and 10 ‘suites’ on top of the unused plates are also printed.

In December 1948 the editions Jean Porson publish Candide, with 46 lithographs in black illustrating the book. 10 ‘suites’ on top of the illustrations from the book, and 10 ‘suites’ on top of the unused plates are also printed.

On December 24, the Gazette des beaux-arts reports “illustrating the text of Candide, which is one of the most admirable work by Voltaire, Clavé embroidered images in his lithographs in black and white, which are admirable of taste and psychological penetration. His style seems grainy and translucent, just like rare porcelain. “ A few days later the Combat also evokes “Clavé’s lithographs for Candide, which are truculent and full of verve”.

The vision of the world of Thunder-ten-Tronckh that Clavé draws is only composed of closed gates and of the kiss between Candide and Cunégonde, which throws the young hero out of his “original paradise”.

The artist tends to illustrate the terrible initiatory adventures during which Candide discovers what “real life” is. Featuring war, violence, barbarism, horrors of all kind, the lithographs are not sparing any character, and are neither complaisant nor displaying demonstrative aestheticism. He mixes a classical approach with a disenchanted eye in his compositions. No cry of horror resonates; the highlight is rather put on a faint and absurd barbarism with these hand-to-hands, which are warlike, sexual and tragic. Candide himself is incapable of being satisfied with the Eldorado, and is represented by a melancholic gaze when returning to Europe to seduce Cunégonde with the help of his two sheep carrying precious stones and gold. This melancholia anticipates his final disappointments and engages the reader in calling into question his own illusions.

The universality of the tale is built on timeless themes such as evil, war, religion and the role of women, but Clavé just like Voltaire avoids any moralism, and rather tries to catch the reader with a bitter laugh. His lithographs in black are masterfully illustrating this initiatory journey and are an invitation to introspect.

For more information on the book for bibliophiles and the printed work of Antoni Clavé, get the catalogue raisonné here.